GRACE LA RUE: And Her Inkey Boys

Part of the Ziegfeld Follies. A singing star of the 20s. A musical comedy headliner on Broadway. She is reputed to be the first woman to earn over $40,000.00 a week in adjusted dollars in 1907. She intro black culture to white audiences!

This extraordinary woman was born Grace Parsons. But such a name would never work on Vaudeville, dispute her talent. So, she adopted the more exotic name of Grace La Rue. And with that name, she became part of the Ziegfeld Follies, A singing star of the 20s. A musical comedy headliner on Broadway. She is reputed to be the first woman to earn over $40,000.00 a week in adjusted dollars in 1907. [1] She made millions. Ironically, in retirement, she filed for bankruptcy with only $600 to her name. Her story is one of hard work, fame, and misfortune. The irony of her life is that she may never have realized the culture-shifting good she had done. This is her extraordinary story.

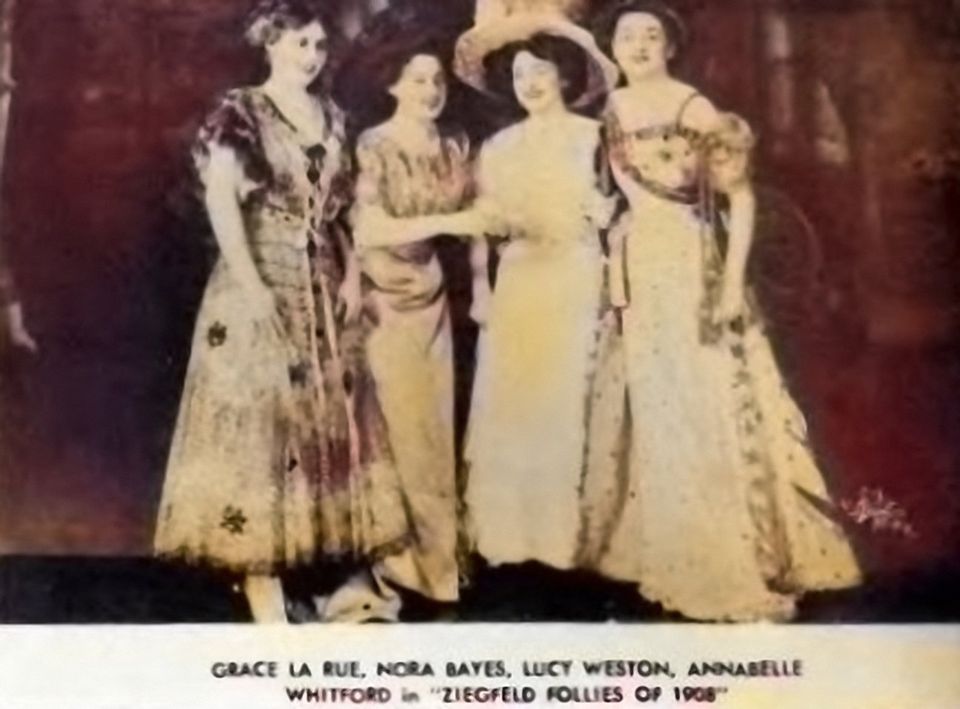

“Born

on April

23, 1882, i

n the poverty of a Missouri farm not far from Kansas City. But poverty would

not stand in her way. She knew how to sing and got the best training she could

get. Grace began her stage career at the age of nine in the Shakespearean

repertory. Her first Broadway engagement was in “The Tourist” with famed Julia

Sanderson and Lillian Lorraine in 1906. Then the following year she was

featured in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1907 and 1908. [2]

Her assent was rapid and highly successful.

Grace

La Rue recalled, “When I was 11 years old as a child soprano, singing the

Psalms at the Grand Avenue Church, Kansas City, and I made my theatrical debut

one year later in the same city, as a page in Julia Marlowe’s production

of ‘As You Like It.’ My initial traveling engagement came the following

year when the Milton Nobles stock company signed me up to play boy parts. But alas, before two weeks

had passed I experienced such a teary attack of homesickness that I was

promptly sent home to mother.

“And there I stayed very willingly until the call from a stock company in Pittsburgh. From playing boy and girl parts with this organization I went to Denver for a dramatic stock season. And then I retired from the stage forever… and seriously committed to the study of music. But in 10 months I was in Vaudeville.” [3]

VAUDEVILLE

Vaudeville

is a live variety entertainment show popular chiefly in the US in the early

20th century, featuring a mixture of specialty acts such as comedy, song and dance. [4]

The early 1900s was the time before television, broadcast

radio and even movie theatres. Going out was pretty much confined to shopping,

church, public meetings, and Vaudeville.

Is it any wonder that Vaudeville was so popular? Preachers felt the competition and often railed against it. Vaudeville,

however, was generally family-friendly, with perhaps some occasional risqué

humor as you might expect in a PG-13 movie of today. Promoters, after all, wanted

the maximum attendance for maximum profits. There was another form of Vaudeville

called ‘Burlesque’ which could be the more R-rated form of variety show often found

in cabarets and clubs, as well as theatres, and might feature bawdy comedy,

saucy music, and female striptease. [5]

Grace

La Rue was ideally suited for Vaudeville. She could sing, dance, act, and even developed

an acrobatic-dance act. [6]

Her singing voice was considered one of the best

in the world.

Racial

bigotry was huge at that time. Blacks had nearly no place in the Vaudeville,

especially in white areas. These were the black-faced minstrel days, that is,

white people with blacken faces as black people. Some Vaudeville performers refused

to appear on the same stage with actual African-Americans. It is, therefore,

most significant that Grace La Rue began her Vaudeville career performing with

a black comedy team known as the Inkey Boys.

Oddly, for her and them it worked. In

fact, audiences loved it. A beautiful and talented white girl performing with an

actual African-American comedy team filled the seats. Grace La Rue is to be

commended for her step outside the box of convention and thus helping to open

the door for other black artists to perform before a white audience.

The

situation was that she needed them more than they needed her specifically. As

one report stated it, “Grace La Rue is accompanied by two of the brightest

colored boys seen on the local stage for

some time. That is all that saves Grace, for she has no native ability.” [7]

There

was at that time an Irish Vaudeville team known as the “Burke Brothers” and

they fashioned an act with a donkey named “Wise Mike.” They would ask their funny little donkey questions and it

would respond with hilarious comebacks. It was highly successful

In

1898 the Burke Brothers were cast in the Knicker-Bocker Burlesquers along with La

Rue. This may have been their first experience together. While this burlesque

show included a “female contingent comprised of the fairest specimens that ever

stepped through the old stage doors,” La Rue didn't appear as one of these showgirls. But, rather as a comedic actor where

she could showcase to her song and dance. [8]

La

Rue was teamed up with them. The Burke Brothers had become known as “the

premieres of all comedians” writing, producing and starring in their own

productions. [9]

At first, La

Rue had supporting roles in their shows, but she soon became a headliner [10]

and especially when she performed with her Inkey Boys.

This prompted her to cancel her management contract with Klaw & Erlanger. [11]

She was doing well enough on her own with the Inky

Boys.

Grace

La Rue and Charles H. Burke became close. Some false reports claimed they

married. However, they may have been romantically linked. She referred to him

as “another optimistic soul like myself.” [12]

To capitalize on their comedic chemistry, Charles

broke, for a while, from the Burke Brothers and Talking Mike gig and in 1903 formed

a Vaudeville act with La Rue and the Inkey

Boys. It was a great success. The Hartford Courant reported, “Charles Burke is

funnier than ever and has made a hit with Grace La Rue and the Inkey Boys.” [13]

The Evening Journal out of Wilmington, Delaware

wrote, “Burke, La Rue and The Inkey Boys …introduces a line of comedy that is

refined and wholesome and so conspicuously good that everyone enjoys it.” [14]

Unfortunately,

the press often referred to the Inkey

Boys, because they were black, as pickaninnies, which was the dominant racial slur

and caricature of Black children for most of America’s history. [15]

Despite the demeaning racial attitudes and stereotyping, La Rue continued to perform with them and to surprisingly great box office. The

songs La Rue sang with them were referred to as “Coon Songs.” [16]

Later, Florenz Ziegfeld was to promote black talent

as well, especially Bert Williams, despite social norms of the time. And, by

the way, both Ziegfeld and La Rue found great financial success in doing so.

They performed together until La Rue got the call form Ziegfeld to join the Follies in 1907. La Rue left the group, but Charles and the Inkey Boys continued as just “Burke and the Inkey Boys.” [17] But then after 1908 little mention is made of either in Vaudeville. The act apparently didn’t seem to work as well without her. Or, perhaps it all ended because they were just burned out after 4 years of the same old act with little change.

1907 ZIEGFELD FOLLIES

She

recalls, “I stayed in Vaudeville until I became a headliner, then I left it for

a prima donna role in ‘The Follies of 1908’” [18]

(Note: Prima Donna means leading female singer).

Ziegfeld paid her well for her singing voice, she is reputed to be the first woman to earn

over $40,000.00 a week in adjusted dollars in 1907. [19]

For

the 1907 Follies, she played Pocahontas, and, of course, she sang. Her

beautiful voice was the very thing Ziegfeld

hired her for. [20]

She continued in the Follies through 1908. And she may have continued, but she fell in love with Byron Chandler the “Millionaire Kid” [21]

THE LONG ENGAGEMENT

Byron Chandler, the “Millionaire Kid,” was the son of a former Governor of the state of Vermont. It was a wealthy family. His father was also the head of the largest bank in New Hampshire. Besides all this, the family was very religious. They attended church every Sunday. They were devout Puritans. But, Byron didn’t seem to connect with the family religion. He later spoke of the money he received as an allowance growing up as being subversive. “I had an allowance of hundreds of dollars where other boys received only dimes and quarters.” When he inherited a million dollars when his father passed on he became popularly known as the “Millionaire Kid,” a knick-name that came about earlier when he was exactly that, a kid. He first came to public attention when he became the first person in Boston to own a car. He spent tons of money on his friends and loved to put on huge lavish parties flowing with the finest campaign. He said Broadway had won over the Governor’s son. He was a sucker, he passed out money to friends like it was going out of style.

“Gold diggers?” asks Brian Chandler, “I wonder why they tie that name to women. The way some of my money went, my ‘friends’ might as well have worn a mask, shoving a gun in my side and rolled me for it. ‘Good old Broadway!’ The man who first wrote that into a song must have lived in Des Moines and never have been east of Chicago.” [22]

La Rue and Chandler first met in Chicago while she was performing “Nearly A Hero” in which La Rue was the leading lady. [23] It was an instant attachment. They went everywhere together. The press was always near. In 1908 the now famous girl from the Follies was seen registering at the Auditorium Hotel in Chicago with Chandler. The clerk at the hotel, attempting to protect them, said they had been married. In those days, of course, sleeping in the same room was something you did after marriage. People did a lot of sneaking around as you might imagine. When the press asked the couple if they had married, they responded “No.” But, they never said anything about being together in a room. [24]

La Rue seemed to like complicated men. Chandler had an army of adoring stage beauties that he spent money on. He had been married to Grace Steecher in 1902 when he was 22. Steecher sued for divorce citing his fondness for drink and other women. Additional Mrs. Edith Roberts, of Manchester, who alleged his attention to her daughter had resulted in $20,000 damages to the young woman. [25] Steecher settled quietly through the secret divorce system in New York that the rich took advantage of. [26] And, there was the $10,000 (that’s $245,000 in today’s money) suit from actress Miss Joan Swartz for breach of promise. [27] Ultimately, Chandler would be married and divorced four times and sued for alleged breach of promise twice and would take his life by suicide in 1942. He was complicated.

Despite all the obstacles and red flags, La Rue married him.

MARRIED LIFE

Their 1909 marriage happened in London, England. Naturally, their honeymoon was in London and Paris. Nothing was too good for her. He burned through money while in Europe on every extravagance possible.

But why marry in London? Because the former Mrs. Chandler’s divorce decree forbid Chandler from marrying during her lifetime. [28] So, they couldn't do it in the USA, they did in the UK.

While in Europe La Rue appeared in many great venues, bolstering her renown.

She had become so famous, in fact, that when she reported to Scotland Yards that her jewels and money, valued at $7,000 (that’s $178,492 in today’s money), had been stolen from her hotel room while she was performing at the Palace Theatre in London, it made worldwide news. [29]

Byron Chandler became her financial backer for plays they now produced together. But despite the money backing, not all shows were successful. The St Lewis Dispatch reported that the Chandler backed [30] “’Betsy’ bores its Garrick audience. Grace La Rue has an unsatisfying play.” [31] And the lifestyle of wine, woman, and song for The Millionaire Kid had kicked in again.

The so-called ideal husband and wife team of money and talent was beginning to crumble. [32]

THE LONG DIVORCE

La Rue could be tough. Grace won a 1910 verdict over playwright George V. Hobart for not delivering a play she had paid him to write for her. [33] He had to pay her $8,423, in today's money. [34]

And she was just as tough on Chandler. La Rue filed for divorce in 1914, alleging that Chandler was unfaithful and that he beat her. She was tough taking decisive action.

The Millionaire kid was not too happy with the whole divorce proceedings. [35] He denied ever being violent and said she would get nothing from him. “I guess Grace is out for the coin,” he said. “She has plenty of money and a good theatrical engagement besides. She says I threatened to shoot her. That is simply ridiculous. Why, I have always loved, honored, and respected her.” [36]

He even tried to weasel out of responsibility to La Rue by claiming “that he was not legally separated from his first wife at the time he paid court to Miss La Rue. He, therefore, said he considered his marriage to her invalid.” [37] The claim didn’t fly.

A few months later in May of 1914 La Rue Chandler announced his intention to marry a much younger Hilma A. Nelson. [38]

Crazy as it might seem, Grace, reconciled with the Millionaire Kid two years later in 1917, settling their matrimonial differences. [39] This comes after he inherited another million from his Grandmother [40] and made a killing on Wall Street. [41] Apparently, a private financial deal was stuck, and all was good between them. [42]

Despite everything, La Rue continued strong in her career.

Modeling clothing was now a part of her shows. Women came to her shows not just to be entertained but also to see the latest fashions. La Rue did not disappoint. Some of her clothes came from Paris, some from New York and some she made herself. “At the international Fashion Show at New York La Rue was claimed to be the best-dressed woman in the world.” [43] About her performance with high fashion, she said each dress she had created was to “serve as an expression of the song she is rendering.” [44]

THE NEW MAN

Whether it was Charles Burke, Florenz Ziegfeld, or The Millionaire Kid, it seems La Rue always needed a powerful and influential man in her life. Perhaps she was never fully aware of her own power. After all, these strong and influential men were also drawn to her as well. She was in her own right a powerful and influential woman.

There was no man she ever fought so hard for than popular actor Hale Hamilton. She fought off all foes, married him and was with him until the day he died.

It all began in 1918 when she began dating Hamilton. By 1919 she was appearing in productions with him. [45] Even though he had been married twice before, [46] La Rue married Hamilton in 1920. [47]

Hamilton had been married to actress Myrtle Tannehill for 6 years, and they had divorced 2 years previously in 1918. But then in 1920 Hamilton’s ex-wife drops a surprisingly unexpected lawsuit on Grace La Rue for $100,000 charging alienation of affection. That would be about $2 million dollars today. She claimed that her ex-husband had first met La Rue in 1908 and “by giving him money and following him about the country, weaned him away from her.” [48] She also falsely claimed that La Rue was still married to The Million Dollar Kid. To complicate things further showgirl Luella Gear claimed she had been the wife of The Millionaire Kid. [49]

The only thing that was running smoothly at the time was the La Rue and Hamilton production of “Dear Me.” It was a huge success. [50]

THE FINAL CURTAIN

How this whole mess was finally resolved isn’t totally clear due to the secret legal settlements of that time. And life went on, with La Rue slowly fading from public memory. Every once and a while there was a News item about La Rue. She claimed that color can talk. [51] She developed a corset for slender and middle-weight women. [52] And it was reported that the Prince of Wales liked Grace La Rue’s golden voice [53] so much that he requested an encore of her song “What’ll I Do” two times. [54]

Between October 1922 and 1923 she played successfully at the Music Box, New York, in Irving Berlin's second Music Box Revue. She was back in London again at the Coliseum in the summer of 1924 in a sketch, Dangerous Advice with her husband, Hale Hamilton. Returning to America, the fading La Rue appeared in productions such as The Greenwich Village Follies (Winter Garden, New York, 1928) where she was limited to two songs.

By the early 1930s, she was living in retirement in California, where she made a brief appearance in Mae West's film “She Done Him Wrong” (1933). [55] In her second and final screen appearance, she played herself in Bing Crosby’s “If I Had My Way” (1940), as a salute to old Vaudeville.

The truth was that the day of live stage performances had given way to motion picture theaters. Even though variety shows will always be with us, Vaudeville had seen its better days. She was never again the headliner she had been. Her large amounts of income had ended. In 1937 she and her husband filed voluntary bankruptcy in federal court listing assets of only $600 and insurmountable liabilities of $21,212. [56]

The Millionaire Kid went on to divorce his third wife, Luella Gear. Then marry Betty Jean West, resulting in his fourth divorce in 1941. As one newspaper summarized his life, “Byron Chandler’s pocket bugging with money seem never to have given him a permanent hold on the joy he started confidently in pursuit of so many years ago.” [57] He committed suicide in 1942 at his Palm Beach estate. His body was found floating in Lake Worth with a bullet wound to the chest. [58]

Finally, in 1956, the “Ziegfeld singing star of the ‘20s Grace La Rue Hamilton” [59] passed away at age 75 in a Peninsula hospital [60] shortly after the death of her beloved husband, Hale Hamilton. In her final days, she had written an autobiography that was never published and is now probably lost. It was named after her biggest successful show “Dear Me.” [61]

The show “Dear Me” was about writing a letter to yourself. The thoughtful premise was: “When you have been down-hearted, discouraged or rebellious, have you ever tried writing yourself a letter… and offering yourself a remedy? No! Try it at once! …and see how quickly your viewpoint of life will change.” [62]

We will never know what Grace La Rue wrote in her “Dear Me” autobiography, but she was probably unaware of her greatest contribution to the American stage. And that is, in an era of extreme bigotry against blacks she mounted a successful career by teaming up with two talented black performers and entertained white audiences. She was one of those daring performers who helped introduce black culture artists to a larger audience.

Like Grace La Rue, often the good things we do go unnoticed, even by ourselves. Take a moment and write that Dear Me letter to yourself. You may be surprised as you discover the real you. The good you!

___________

FOOTNOTES

[1] The Kansas City Times. Wed. Mar. 14, 1956. Page 1

[2] The Morning Call (Penn.) Sunday Nov. 27, 1921. Page 16

[3] The Indianapolis Star (Ind) Mon. Nov 13, 1911. Page 7

[6] Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express (NY) Sun. Oct 27, 1901. Page 23

[7] Buffalo Courier (NY) Sun. Nov 22, 1903. Page 34

[8] The Boston Globe. Sun. Feb 13, 1898. 1898

[9] The Dayton Herald Wed. Nov 7, 1900. Page 5

[10] Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express (NY) Sun. Oct 27, 1901. Page 23

[11] The Philadelphia Inquirer. Sun. Sep 20, 1903. Page 32

[12] The Indianapolis Star (Ind) Mon. Nov 13, 1911. Page 7

[13] Hartford Courant (Conn.) Wed. Oct 28, 1903. Page 7

[14] The Evening Journal (Delaware) Wed. Jan 24, 1906. Page 6

[16] The Buffalo Enquirer (NY) Tue. Nov 24, 1903. Page 3

[17] The News Journal (Del.) Tue. Feb 5, 1907. Page 6

[18] The Indianapolis Star (Ind) Mon. Nov 13, 1911. Page 7

[19] The Kansas City Times. Wed. Mar. 14, 1956. Page 1

[20] Evening Star (Wash DC) Tue. Sep 17, 1907. Page 16

[21] Santa Cruz Evening News (Calif.) Tue. Dec 29, 1908. Page 6

[22] Buffalo Courier (NY) Sunday Feb. 4, 1923. Page 57

[23] Chicago Tribune. Sun. Jul 16, 1911. Page 2

[24] Santa Cruz Evening News (Calif.) Tue. Dec 29, 1908. Page 6

[25] The Buffalo Times (NY) Wed. Dec. 23, 1908. Page 3

[26] St. Louis Post Dispatch (Missouri) Sun. Dec 12, 1909. Page 26

[27] The Evening Sun (MD) Wed. Aug 20, 1913, Page 1

[28] The Stark County Democrat (Ohio) Thu. Aug 19, 1909. Page 1

[29] Palladium Item (Ind,) Wed. Aug 20, 1913. Page 6

[30] New York Herald. Wed. Jul 31, 1918. Page 8

[31] St. Louis Post Dispatch (Missouri). Tuesday Nov. 7, 1911. Page 8

[32] New York Tribune. Thu. Apr 2, 1914. Page 3

[33] The Wichita Daily Eagle (Ks) Sunday June 26, 1910. Page 20

[34] The award was $316.90 in 1910

[35] New York Tribune. Sat. Jul 11, 1914. Page 4

[36] The New York Times. Thu. April 9, 1914. Page 6

[37] The Washington Herald (DC) Thu. Aug 1, 1918. Page 6

[38] The Washington Herald (Wash. DC) Sun. Dec 5, 1915. Page 27

[39] The Cincinnati Enquirer (Ohio) Thu. Jan 4, 1917. Page 4

[40] Chicago Tribune. Sun. Jul 16, 1911. Page 2

[41] Actress Returns to ‘Millionaire Kid’ — Los Angeles Herald 4 January 1917

[42] Actress Returns to ‘Millionaire Kid’ — Los Angeles Herald 4 January 1917

[43] Harrisburg Daily Independent (Penn.) Wed. Jan 26, 1916. Page 8

[44] The Courier (Pennsylvania) Sunday, Jan. 23, 1916. Page 6

[45] San Francisco Chronicle. Sunday, Aug. 3, 1919. Page 4

[46] The Gazette (Montreal, Canada) Tue. Jun 1, 1920. Page 13

[47] The San Francisco Examiner. Sat. June 5, 1920. Page 2

[48] Buffalo Courier (NY) Thu. Mar 4, 1920. Page 1

[49] Daily News (NY) Wed. Jan 28, 1920. Page 7

[50] The Daily Times (Davenport, Iowa) Mon. Sept. 6, 1920. Page 14

[51] The Washington Herald (Wash. DC) Sunday, Dec.11, 1921. Page 33

[52] Joplin Globe. Sun. Mar 19, 1922

[53] Iola Daily Register and Evening News (Kansas) Thu. Sep 4, 1924. Page 4

[54] The Buffalo Commercial (NY) Sat. Sep 6, 1924. Page 7

[56] Vidette Messenger of Porter County (Indiana) Thu. Jan 14, 1937. Page 1

[57] San Francisco Chronicle. Sunday Nov. 25, 1923. Page 7

[58] The Hutchinson News (Kansas) Mon. Dec 21, 1942. Page 7

[59] The Blizzard (Pennsylvania) Wed. March 14, 1956. Page 7

[60] The Kansas City Times. Wed. Mar. 14, 1956. Page 1

[61] The Times (San Mateo, CA) Wed. May 23, 1956. Page 2

[62] Iowa City Press Citizen (Iowa) Wed. Sept. 1, 1920. Page 6